As emerging technologies continue to transform products and services at a fundamental level, they simultaneously open new arenas of exploration for designers. Indeed, technology is not just a tool but a powerful “material” at the intersection of art, science, and computing—ready to be molded for creative expression and practical innovation [2, 3]. Yet, Indian design education is still grappling with how best to integrate these new possibilities into its curriculums. There is growing unease and confusion regarding adopting emerging tools, teaching methods, and evolving course structures, which must adapt to the demands of a rapidly changing technological landscape [1 – 6].

The promise of new computational realities (e.g., GenAI, IoT, Quantum Computing, etc.) and evolving digital platforms compels educators to reconsider design pedagogy. India’s designers need to see technology not as an abstract “black box” but as a tangible, pliable medium—like clay, wood, or textiles [5]. In an early experiment conducted by us, when third-year product design students were introduced to creative coding and physical computing sessions, for instance, many discovered that electronics and programming could be as expressive as traditional craft, bridging the gap between scientific logic and artistic exploration [3]. Beyond mere software usage, emerging technologies broaden students’ capacity to prototype interactive objects, craft experiential solutions, and refine products in real-time. In practical terms, this suggests pushing technology components—like creative coding or tangible interfaces—into the core of design syllabi rather than treating them as optional electives.

However, the future of Indian design education does not rest on technology alone. A rich, indigenous tradition of India’s design wisdom remains under-explored in contemporary curricula [8, 9]. For example, hyper-hybrid creatures (i.e., Ihāmṛga) in ancient Indian art showcase an intricate understanding of form, symbolism, and storytelling [10]. Such local aesthetics and knowledge systems hold centuries of embedded design thinking, where religious, social, and ecological contexts drive creative forms. By infusing classroom projects with references from Indian craft traditions, ancient texts, or regional artistic motifs, educators can help students discover culturally grounded solutions relevant to India’s own needs and values. While this is often discussed and practiced in forms of class assignments and classroom discussions, a formal introduction and dedicated courses are in paucity in many design schools.

Embracing India’s heritage calls for a deeper, decolonized perspective in design. Scholars have noted that many Indian institutions originally modelled their design faculties on Western pedagogies and frameworks [5, 6]. This approach can unintentionally side-line local cultural contexts. A decolonized curriculum would instead foreground indigenous insights—treating them as primary sources of innovation rather than historical curiosities. Such a curriculum recognizes that India’s design landscape was never merely an imitation of Western trends but is shaped by native philosophies, vernacular practices, and a collective sense of aesthetics that differ from region to region. Teachers must encourage critical reflection on how foreign influences mesh with local priorities, ensuring that technology adoption coexists alongside a celebration of Indian culture and knowledge systems.

To catalyze this shift, academic leaders can begin by weaving projects on creative coding and engineering into the foundational years of design school, while simultaneously championing early engagement with indigenous crafts, scriptural design references, and local artisan communities [3][7]. Collaborative endeavours—where digital experts partner with craft practitioners or heritage historians—also enrich the learning process, sparking holistic, interdisciplinary thinking. As students practice new technologies hand in hand with traditional materials, they learn that innovation can be both cutting-edge and deeply rooted in local contexts.

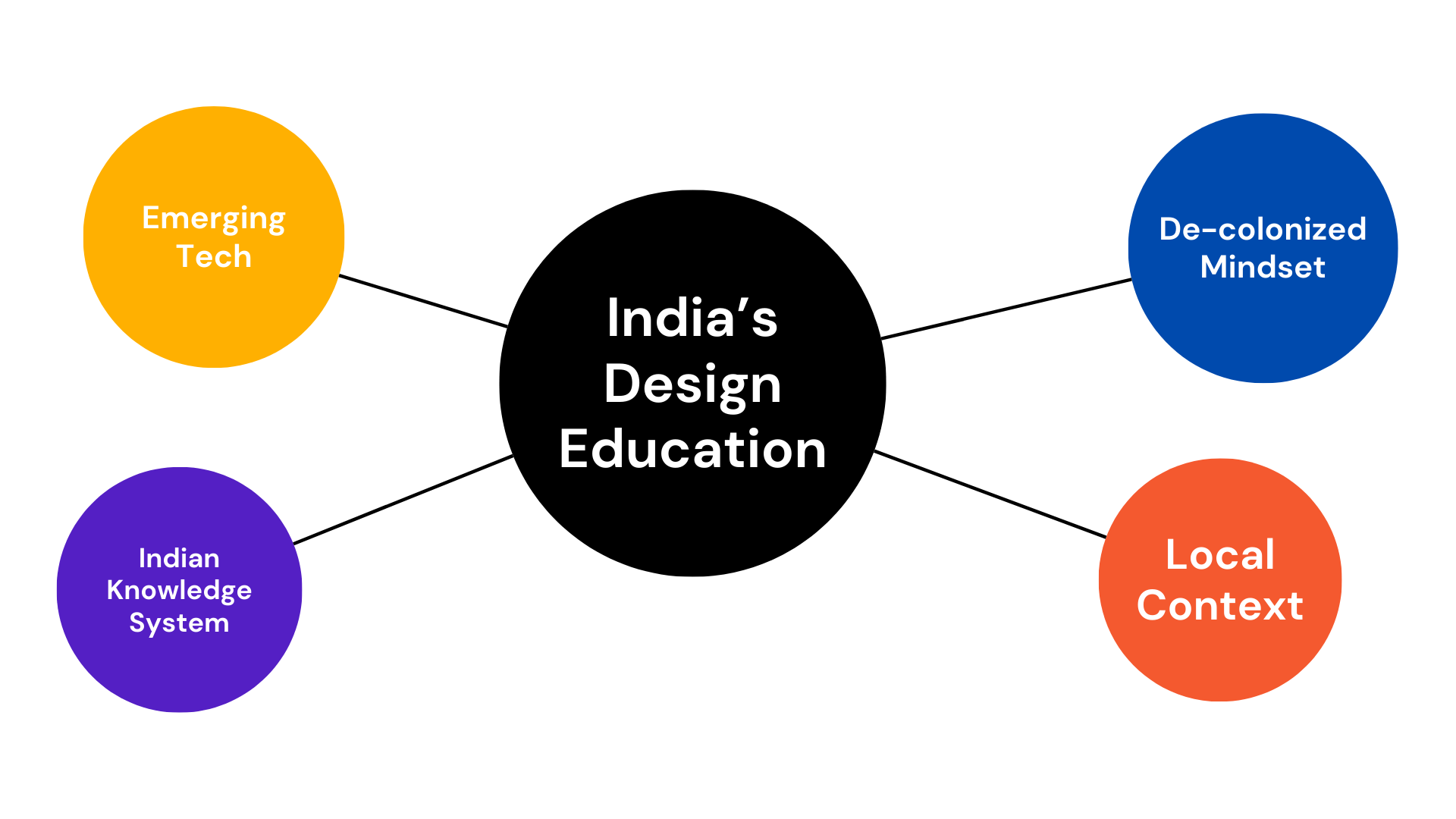

Ultimately, the future of design education in India will be shaped by our ability to integrate three vital threads: Emerging Technologies, Indian Knowledge Systems, and a Decolonized mindset. This vision upholds technology as a material for exploration, honors the genius of Indian heritage, and unshackles pedagogy from inherited colonial frameworks [4 – 6]. In doing so, design schools and students alike can forge fresh paths—ones that keep pace with global advances while staying firmly anchored in India’s cultural richness.

Reference:

- M. P. Ranjan, “Lessons from Bauhaus, Ulm and NID: Role of Basic Design in PG Education,” in DETM Conference, NID Ahmedabad, 2005, pp. 1–15.

- P. Yammiyavar, “Innovation Management: Teaching the art of innovation and its management to creative designers,” in Indo-US Workshop on “Product Design – Impact from Research to Education to Practice,” 2010, pp. 255–264.

- P. Yammiyavar, “Status of HCI and Usability Research in Indian Educational Institutions,” in Human-Computer Interaction and International Public Policymaking, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010, pp. 21–27.

- S. Tewari, “The Design Journey of Prof. Sudhakar Nadkarni,” Design Journal, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 759–765, Sep. 2018.

- S. Balaram, “Bauhaus and the Origin of Design Education in India – Articles – bauhaus imaginista.” [Online]. Available:

http://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/3268/bauhaus-and-the-origin-of-design-education-in-india

[Accessed: 27-Jun-2019]. - S. Balasubrahmanyan, “Moving Away from Bauhaus and Ulm – Articles – bauhaus imaginista.” [Online]. Available:

http://www.bauhaus-imaginista.org/articles/4197/moving-away-from-bauhaus-and-ulm

[Accessed: 27-Jun-2019]. - P. Yammiyavar, “UE-HCI Lab.” [Online]. Available:

http://iitg.ac.in/uelab/about.html

[Accessed: 28-Jun-2019]. - C. Maurya and N. Maurya, “Ancient Indian ergonomics wisdom and its contemporary significance,” Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 245–258, 2022.

doi: 10.1080/1463922X.2021.1898061 - A. Srivastava and S. Atreya, “Does the ancient Indian practice of Yagya reflect critical product design attributes?: A Designer’s perspective,” Interdisciplinary Journal of Yagya Research, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 13–20, 2023.

doi: 10.36018/ijyr.v6i2.111 - N. N. Hadap, “Design Thinking Process and Ideation Of the ‘Mythical Hyper-Hybrid Creatures’ in Ancient Indian Culture: A Study,” International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education (INT-JECS), vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 2595–2605, 2022.

doi: 10.9756/INTJECSE/V14I4.358